The Mysterious Little Christmas Tree

/Kiama-Gerringong, NSW

For you beautiful heart whoever you might be

“Do not forget to show hospitality to strangers, for by so doing some people have shown hospitality to angels without knowing it.” (Heb. 13:2)

“Everything in this world has a hidden meaning.” (Nikos Kazantzakis)

“There are millions of homeless people in the world because humanity does not have a proper conscience.” (Mehmet Murat ildan)

“Sometimes it's easy to walk by because we know we can't change someone's whole life in a single afternoon. But what we fail to realize it that simple kindness can go a long way toward encouraging someone who is stuck in a desolate place.” (Mike Yankoski)

There are moments in our lives that have a deeply moving effect on us. They manifest a change in us. We normally remember these moments for the remainder of our lives. They can be sad experiences brought about by some devastating event or they can be joyful happenings which we might normally recollect as anniversaries through the passing of the years. Then there are those “moments” which can leave us spellbound and spine-tingling with awe. Think back, if you will, to some of those occasions. Perhaps it was at the Louvre in Paris when you first came ‘face-to-face’ with Leonardo da Vinci’s famous ‘Mona Lisa’. Or maybe it was that time in London’s National Gallery when you saw Rembrandt’s ‘Belshazzar’s Feast’. Something inside of you is viscerally shifted, your response to such artistic human endeavours touches you to the core. And what of such places which have been flamed by the divine: the Temple Mount; the Church of the Holy Sepulchre; the Blue Mosque; the Bodh Gaya. So then it can become too easy [or habitual] to dismiss those occasions which might fill us with a different sort of awe, and to oftentimes pass them over thinking, yes, quite lovely, but way too mundane.

Source: https://www.kiama.nsw.gov.au/Council/Projects/Hindmarsh-Park-upgrade

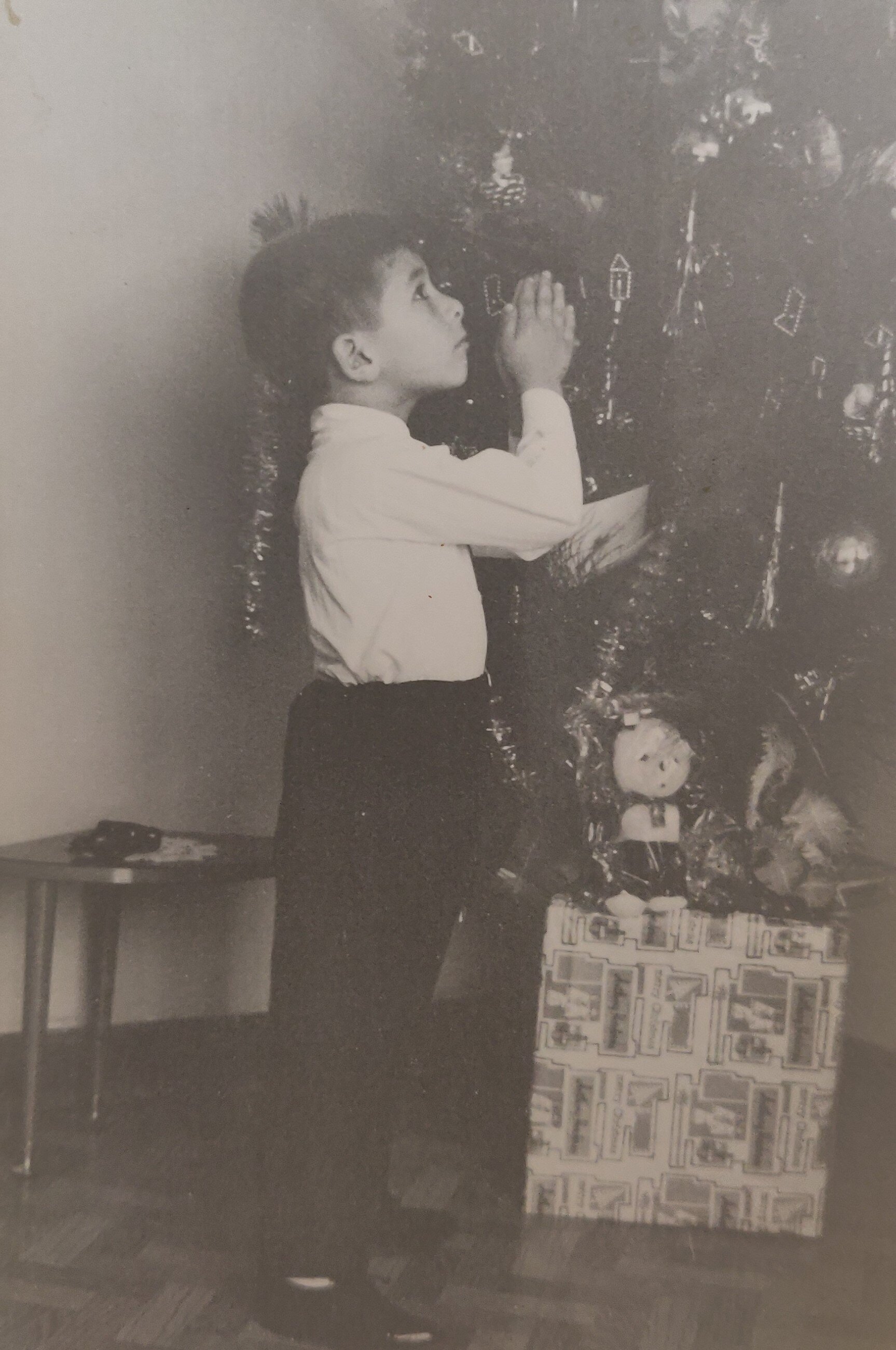

Today, on my early morning walk down by Kiama’s scenic harbour in the company of one excitable Mishka, the canine member of our family, we came across a profoundly moving sight. In a rarely used bus shelter on the lower end of Hindmarsh Park,[1] what I saw brought me to tears and what is more, touched me no less than those times when I stood in awe before the sublime artistry of our great masters. What did we see? In the shelter were two suitcases and a blue trolley with an umbrella strapped to its side. Through one of the side glass panels my eye caught a shimmering object on the bench. It was a small plastic silver star. It was placed there with a purpose as the surrounding evidence would show. Below the star itself, was a colourful [but broken] toy windmill. Little pieces of twig were arranged strategically around the windmill’s wooden blades. Attached to the twigs were a variety of shells as ornaments. All this industry was laid out on the top half of the bench. Clearly, this was a Christmas tree. I wondered which sensitive heart was behind such an honest creation. What might have been this person’s story? My eyes welled up as other parables of a similar sort came to me. I thought of the symbolism of what I had just seen and of the significance of such an act by someone who had obviously lost a lot somewhere along the way. I reflected on my comfortable life and my home which lacks nothing. And maybe once or twice before I had felt such raw and brutal proximity to that origin myth and of the implications of the exile from Paradise [if you still believe in such things].[2] There is much I would have liked to have said to this ‘angel’. To have embraced them and for my tears to have spoken to their heart when my words would only have meant something if I was to hold them back anchored to my tongue. I was defeated by the untold grace of this unexpected encounter. This work of angelic inspiration poured from the purest gratitude is reminiscent of the “widow’s offering” who gave all she had from her poverty (Mark 12:41-44). And no less magnificent in its intent than the breathtaking creations we come across in the great museums of the world. I was dwarfed by this humble little Christmas tree. And religion, at least of the rubric kind, had little to do with it. It was the ‘tremendous mystery’ of the hour.

Postscript

The next day, on the afternoon of the 14th, Mishka and I were again out walking down at the harbour, which on our return will take us back past Hindmarsh Park. As we approached the bus shelter which the day before with its mysterious little Christmas tree, had opened up that flood of emotions in my heart, I could see something circular, like a bright large orange ball. Now, I wondered, what could that be? The closer Mishka and I got to the bus shelter, the one which housed this mysterious little Christmas tree, it became clearer that the bright large orange ball was in fact a small furry head. I once again peered through the glass window. It was a teddy bear! I smiled. It was perched on the window’s ledge watching over the Christmas tree with its hands outstretched as if in the orans position, like a ‘platytera’ on a half-dome. At the same time its eyes, which were still intact despite the unmissable signs of age on the body, were also surveying, protecting the bags and blue trolley from the day before. On the way back to the car, Mishka and I paused. We turned to look at that fantastic spot from where only minutes ago we had walked past. I understood the manger, or better still, the creche in the traditional Nativity imagery in yet another light and felt grateful beyond words to this travelling soul. Saint Seraphim of Sarov, Leo Tolstoy, and all the others, and those who came before, the Prophet Isaiah, and after them, Gwendolyn Brooks, were right, of course. Real beauty which is neither artificial, nor affected, is more often hidden, and waiting to be discovered, where you might least expect it. I remember Rembrandt and am struck by that spellbinding awe, but this recall does not comfort my spirit when it is aching. On the other hand, this ‘wandering angel’, already, is comforting my night pains and revealing insights into another, more enduring splendour.

[1] https://library.kiama.nsw.gov.au/History/Explore-Kiamas-Past/Local-history-stories/Hindmarsh-Founding-Orphans

[2] I use the term “myth” here in a similar way to Carl Jung’s conventional interpretation: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1hcogiUUNnM