“No, we did not see him”, said the wife of the concierge, and the moon came out ashen on the hill, I knew he was hiding, but I would have recognised him, from his enormous shroud which touched the edges of the city, and from the sound hole of the violin, which his soul had rolled out, on the night they were trampling on him,

and suddenly I saw him in the room, he was slowly-slowly going up the scaffold, while the lamp of the nightguard was spearing his side, I saw him I tell you, calm and serene, like the dead, who have now rejected pain no longer to be wasted on God,

“open, I cried, they are killing someone in there”, the old woman opened, and he prostate, was licking their shoes, inside the heavens, “we two are left alone” he said, a whisper then came from afar, an irrational nostalgia to again see my father, but the years had passed, and innocence now staggered, like an angel suffering from his wings,

“do not betray me” he said, and then how he opened his coat I saw the demon, which had eaten all of his body, and his head was now balanced on the hand of the anchorite,/ who was praying in the desert.” (T.L., Night Visitor, Metamorphosis)

“Often I like to light the candle for different reasons or to sing in the winter’s night or other times I stand on one leg like an allegory.” (T.L., Discovery, From the Confessions of Mathias X.)

Source: https://theconversation.com/kintsugi-and-the-art-of-ceramic-maintenance-64223

TASOS LEIVADITIS: A Reflection on a Poetic Soul and the Beauty of Kintsugi

For Maria Leivaditis and Vaso and Stelio

and Helen Constanti and Chrysoula Georgilakis

“My dearest Aikaterine and Michael

Moon of twenty days… how the years pass. / For our Tasos I make this reference with slight variation. / Stresses, concerns, running about, / To what end? / “Troubled about many things” indeed. / And so, alas the intervals of silence are prolonged. / Till that time when the final and eternal silence arrives. / However till then receive heartfelt blessings / for Holy Christmas / and the New Year.

Athens 9 Dec. ‘97

I embrace you

Maria Leivaditis”

“I said it at Tasos’ farewell and I’ll say it again here: we who talk about him, not to remember him but because we remember him, we are all his friends, even those who have not met him. Yet, we have not all come from the same roads. They have been different, even antithetical.” (Titus Patrikios)

There are poets I carry on the ‘inside’ of me as well-worn phylacteries

Source: Personal Communications from maria leivaditis to M.G. Michael (M.G. Michael archives).

There are poets I carry on the ‘inside’ of me as well-worn phylacteries; a little anthology of beautiful prayers. Here I want to speak of one in a more personal way. The writer who introduced me to the actual transformative power of poetry, albeit in my mid-20s, and more importantly to the genre’s potential as a genuine force of healing. The poet is Tasos Leivaditis (1922-1988).[1] Like many other wonderful poets of his generation in Greece of the post-World War 2 period, he wrote under the booming shadow of his celebrated compatriot Yiannis Ritsos (1909-1990), who had been twice nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature.[2] In Australia where I live and work, the best example I could give of a poet holding such a huge presence in the sphere of their literary influence would be Les Murray (1938-2019), who had also been short-listed for the Nobel.[3]

“And when I no longer have what else to live with, I will get a big mirror and I will stand on the corners, like those with the scales or the lives of the saints, and there for a few dimes I will let the passers-by be mirrored, seeing for a moment inside the deepness of the mirror/ all of the desert which follows us…” (T.L., The Blind Man with the Lantern, Reflections)

“And if one does not die for the other/ we are already dead.” (T.L., Small Book for Big Dreams, Valuable Verse)

source: H lexi , Afierwma tasos leivaditis, November-December ‘95 Vol. 130, p. 782.

“To my brother Tasos Leivaditis”, Yiannis Ritsos (9.11.89)

“For some time you have been waiting for them with awe./ And they came, your dead/ and they took you in the night’s light rain/…” [4]

“Letter to Tasos” Yiannis Ritsos (21.8.73)

“My dearest Tasouli, days now I have been thinking to write you, because I have missed you very much. And now at this moment the postman knocked on the glass of the window and gave me your letter. Late evening. Outside it is still bright…” [51]

Afterwards would come the years of exile

source: H lexi , Afierwma tasos leivaditis, November-December ‘95 Vol. 130, p. 727.

Tasos Leivaditis was born on the 20th April, 1922, in the working class neighbourhood of Metaxaourgeio, in Athens.[5] It was Easter, so he was given the name Anastasios (from Gk. anastasis, meaning “resurrection”). He was the youngest of five children born to Lysander Leivaditis and Vasiliki née Kontopoulou. His father was a well-to-do wholesaler but the family fell into poverty on account of the war. In 1940 our poet enrolled to study law at the University of Athens. However, the German occupation of Greece in 1941, put an end to these plans and instead he joined the Resistance and EPON [the progressive left youth organisation]. After those terrible years of the Greek civil war,[6] the years of exile would come (1948-1952). Together with many others who held to left leaning ideologies, amongst these his dearest friend, Yiannis Ritsos, he would experience as a political prisoner in Moudros on Lemnos, Ai Stratis, and Makronisos, that had reaped for itself the foreboding epithets “isle of shame” and “hell hole”, the darker side of humanity.[7] His response and resilience to this physical and mental tyranny would inform a great deal of his writing, certainly what is referred to, as the “First Period” (1952-1965).[8]

The world lost one of her most sensitive poetic consciences

Caption: tasos leivaditis. source: copy of photograph sent by maria leivaditis to m.g. michael (M.G. Michael archives).

Under what circumstances I was introduced to the poet, I will leave for another time, except to say it was during a testing hour in my own life when I was a young clergyman and I was left almost entirely isolated from community and friends. Yet, there is another much brighter piece to this story which complements the more difficult one. Through some improbable events I was to share in a beautiful friendship with Maria Leivaditis, the poet’s companion from youth and then beloved wife.[9] We spoke on the telephone and corresponded regularly until her own illness and passing away. Oftentimes, she would post me treasures: copies of the poet’s hand written poems; portraiture drawings of the poet himself from the hand of his adored grandchild, Stelios; [53] photographs of memorable moments; and perceptive pieces of verse written by Maria herself. Sadly, by this time, the poet himself had passed away. Leivaditis died on the 30th October, 1988. It was Sunday morning. He had been admitted to the General State Hospital in Athens where two surgeries for aneurysm of the abdominal aorta failed to save him. The world lost one of her most sensitive poetic consciences. He was sixty-six years old. Given his sensibility it did not surprise his friends, that he had, even if unintentionally, foretold the month and season of his death.[10]

“The calendar will show October -with the withered leaves and the protests.” (T.L., The Blind Man with the Lantern, In Memory)

“He left suddenly, a day in Autumn, on the table he had left a letter “do not send me away” it said, and it spoke about a distant, uninhabited premonition, the lights in the house were on…” (T.L., Night Visitor, The Visitor’s Letter)

“I had to get escape, otherwise I was finished, but the stranger of the station was already waiting for me on the edge of my journey. Which stranger? It was the very same me, defeated and opening the doors on the motionless carriages and I’d come out on the other side of the dream./ Oh! grief, we learnt you from childhood, almost before we were introduced to the world.” (T.L., The Manuscripts of Autumn, Oh! Grief )

“Irrelevant details which make our memories and years more painful, mummified birds, are looking at us now with foreign eyes-/ and yet who was I? a prince of the nothing/ a madman for revolutions and other lost causes/ and whenever the bells would ring I felt that humanity was in danger/ and I would rush to save her./ And when a child looks with ecstasy at the sunset, it is because he is storing griefs for the future.” (T.L., The Manuscripts of Autumn, Sunset)

“When they exiled us from Paradise, Maria was crying. I then took her to the hotel opposite because we had to get on with life. When we came out it was getting dark. Maria caressed her stomach. “There is hope,” she said./ Hope which makes the world even more uncertain.” (T.L., The Manuscripts of Autumn, Hope)

“And as the years pass I become all the briefer, to the point when at the end one word would suffice me: “silence”, like in the hospitals – or “fire!”/ like all my mornings.” (T.L., A Manual for Euthanasia, Oligarchy)

A beautiful bunch of white roses from the poet’s wife and symbols

“His name Jacob, hers the more serene: Maria. They stood upright beneath the trees, with hands clasped…” (T.L., Violets for a Season, Fragile World)

Caption: tasos leivaditis with maria, vaso and stelios. source: copy of photograph sent by maria leivaditis to m.g. michael (M.G. Michael archives).

On the eve of my marriage to Katina (now nearing its twenty-seventh year), we received a beautiful bunch of white roses from the poet’s wife.[11] Over the years she would become one of my most trusted friends. I remember one of her constant admonitions when we would speak: “Michael, be careful of the ‘networks’”. This was a recurring theme in Leivaditis’ work, that is, the corrupt and demoralizing power of the institutional network in all of its many facets. In other words, what we might nowadays call the ‘power elite’. A term made popular by the American sociologist and “political polemicist” C. Wright Mills to speak of the interwoven interests of those in positions of authority. Maria would say we needed to keep a “look-out” for the “hats”. “Metaphorical hats” we would call them! I fondly recall, too, how she enjoyed a play on words I once made when I spoke of “metaphysical umbrellas”! Then we would together laugh. She said it would be a great title for an anthology but later I was happy enough to allow for a friend to make use of this image. Maria had a wonderful sense of humour. The hat and the umbrella are only one of the many metaphoric symbols in the poet’s work which together with ladders, and room chambers, and coffee houses, and gardens, and stars, and moon, and sea, and rain, and dogs, and birds, and mirrors, and windows, and doors, and keys, and train stations, and flags, and calendars, and cemeteries, and Bible, appear throughout Tasos’ writings. A caveat though, not in every instance must we go looking for symbols. Things can be exactly as they are described, that is, a wall can be just that, an ordinary wall. Context plays a huge part in this genre. It is as fundamental to understand the poet’s use of metaphors and similes, the rich imagery and iconic pictures which they convey, as is his conceptual understanding of the ideas of marginalisation, and poverty, and loss, and solitude, and compassion, and justice, and peace, and brotherhood, and motherhood, and poetry, and music, and history, and exile, and hope, and time, and love, and death, and mystery, and God. We should also be careful to discern the ideology behind the many symbols in the poet’s work, to neglect to do so would be to fall into extremes as Apostolos Benatsis reminds us citing various studies.[12] We would be making a mistake to typecast our poet into either the political or religious category. Like all writers he was not only writing in different and oftentimes intense socio-political contexts, he was also evolving himself, spiritually and intellectually. These remain critical elements which Alexandros Argyriou will rightly emphasise in his essay on the character of the poet’s voice.[13] We can agree with Benatsis’ conclusion of Tasos Leivaditis’ underlying consistent vision, which is, “vindication” for the marginalised, presented in changeable literary formulations and ideological perspectives depending on the period of his writing [something similar, let’s say, with Ernest Hemingway’s belief in “the ideas of conservative republicanism”].[14]

source: H lexi , Afierwma tasos leivaditis, November-December ‘95 Vol. 130, p. 810.

“One should not, however, remain only on the poetical transformations in the poetry of Tasos Leivaditis, but to also move much further. The basic essentials of his poetry are Deprivation, Ordeal, and faith in future Vindication. The key characters change, the techniques variable, yet the value system of the poetical subject does not change. His poetical universe remains one. His heroes are in the beginning deprived, they pass through ordeals in military camps and in the alienating conditions of the present, but his poetic subject hopes that at last in the future will come vindication. This vision and this anticipation runs through all of Tasos Leivaditis’ poetry.” [15]

I am, very sad, still and all, that I could not keep a promise which I had made to Maria, to be the first translator of Tasos Leivaditis’ books into English.[16] Yet, I had translated a large selection of his poems which I had at one time planned to publish, or to have at least used in a doctoral study on the poet.[17] Things happen for which we can be entirely unprepared. This I had looked forward to writing in my twilight years, proposing to deal primarily with the metaphysical dimensions of his work and its connection to the magical realism tradition of the Latin Americans and the other source emanating from Kafka and Central Europe. These observable influences are not absent from Modern Greek literature given the tradition of its sensory and figurative language.[18]

“They were the days of that strange trial which made such a noise./ From the morning a large crowd of people gathered in the great hall and the corridors,/ and despite the rain and more people on the footpaths, many avenues around. Everyone remembering their life. Many were crying. Others were inebriated/ and blaspheming. But when the time came and the judges entered/ there was an endless silence. And a little later, after some brief, confirmed, procedure,/ the verdict came. You betrayed: death, was heard the relentless voice of justice./ A wave of relief swept over the crowd. Faraway bells were heard,/ maybe even arrows. But again all things suddenly fell silent as the second verdict was delivered. You did not betray:/ death, once more the relentless voice of justice was heard.” (T.L., Poems, 1958-1964, The Trial)

“And the small, dead servant girl, we once used to lie together, now stretched her hand inside my vigils, to give her a pair of stockings, which I had promised her.” (T.L., Night Visitor, The Cab)

“It is dark. A time when someone asks of themselves what have they done in their life. And the dead have reclined and crossed their hands, as if what they were searching for,/ they now touch, at last, inside themselves.” (T.L., Night Visitor, The Account)

“And here my story would have ended, if at the opening of the door Martha had not appeared - Martha, who had been dead for years. It was too much and the little food which I had for supper I went down and gave it to the dog/ who did not bark at her.” (T.L., Discovery, The Continuation)

“Many times I stopped, suddenly, on the street wanting to remember or often I would turn to see without no one having called me (no one? how gullible we are) -like someone calling from the window “Elias, Elias”, he was wearing a dirty hat and holding a candle, later he came down slowly to the basement, where he stood for a long time/ listening with sobriety to the answer.” (T.L., A Manual for Euthanasia, Eli, Eli…)

“Until later after many ages and so many farewells I arrived at the final border/ in my hands I held my small dead cousin I was taking her to vacation in the unknown./ My eyes were wet as if I had wept over paradoxical books.” (T.L., The Manuscripts of Autumn, Paradoxes)

“A bird sat on the rails of the garden, it said something to the girl of the veranda, but she did not hear. It was buzzing everywhere with cicadas./ And then I thought that there will come a time when I will remember this scene, after many years, and I will weep unconsolably.” (T.L., The Manuscripts of Autumn, Summer)

“But I’m not guilty,” said K. “there’s been a mistake. How is it even possible for someone to be guilty? We’re all human beings here, one like the other.” “That is true” said the priest “but that is how the guilty speak.” (Franz Kafka, The Trial)

My first serious attempts at translating the poet

CAPTION: m.g. michael personal library (gifted by maria leivaditis and helen constanti. to m.g. michael).

If memory does not fail me here, my first serious attempts at translating the poet were originally in the summer of 1989 on a road trip from Sydney to The Entrance on the Central Coast of New South Wales. We felt the tremor from the Newcastle earthquake almost 65 km away. All the while the once paternal relationship with my confessor was now fast deteriorating and I had a good sense of what would shortly befall me. The initial pieces of that tentative effort at translation belonged to one of Tasos’ most referenced collections from his second period, Night Visitor (1972). It is important to mention that Leivaditis’ poems are not ordinarily in traditional poetic form, rather they are pieces of prose of varying length. Similarly, I also recollect those evenings when I made my first rough translations of Les Murray’s poems into Greek. I was in bootcamp in Larnaca, Cyprus, serving in the Cypriot National Guard. The book of poetry was The People’s Otherworld (1983). It was here that I would first discover the mystical Equanimity and its ode to grace.[19] The same with David Brooks, I was in the Illawarra, in a café pouring over his marvellous Urban Elegies (2007), where my first translations of his were made.[20] The task of translating is something that cannot be taken lightly. It is a huge responsibility and a complex undertaking with many variables thrown into the equation. It is vital that one remains as faithful as possible to the original, trying your best to sacrifice only very little of the precise intent of its writer whilst aiming at the same time to lose only a few notes of the ‘music’. That is, to safeguard the ‘style’ [to literally, protect the “pen”], the melody, the manner of the first author.[21] I have thought of the translator as a good drummer, their job is to keep the rhythm and the beat, sometimes the score will allow them to improvise a little, other times they must keep strictly to the drum notation.

“Now that I no longer have anything to hope for, I think of my insignificant life with gratitude, because, oftentimes, not giving me any attention, as if I had never existed, They would reveal themselves, and during the nights I could hear her ring on the marble, no one ever knew which chamber she was in, timid and withdrawn, from that time when she was touched by the incomprehensible and she had left with someone from the churchyard,/ and let the others say that I was left on the margins, what else can one do, except from holding on, with all the temptations, far away from the Great, in this way you communicate by degrees with him in a different way and on the road the destitute, one recognises the other, from their tentative steps, as if they are following their better self, who goes in front.” (T.L., Night Visitor, The One Better)

“In every home, there is an unknown, secret ladder, which would have taken you, perhaps, faraway. But you find it, when you no longer have a home.” (T.L., Night Visitor, The Ladder)

“…the same grace moveless in the shapes of trees/ and complex in ourselves and fellow walkers; we see it’s/ indivisible/ and scarcely willed.” (Les Murray, Equanimity)

“We must continue to speak: although the language we use/ is like sand, it is desire that whets it, that sometimes/ fuses it into glass.” (David Brooks, True Language)

“Translation is a curious craft. You must capture the voice of an author writing in one language and bear it into another, yet leave faint trace that the transfer ever took place.” (Lara Vergnaud, Translation, in Sickness and in Health, 2018)

It was as if the poet was directly speaking to me

Source: Personal Communications from maria leivaditis to M.G. Michael (M.G. Michael archives).

Next to the Apocalypse of John, the terribly misunderstood last book of the New Testament, which shook my soul when I was in my late teens to change the course of my life in ways I could not have anticipated, I had never before experienced such a personal revelation of hope and endurance in reading poetry. Whatever principles of narrative we might apply, it was as if the poet was directly speaking to me. I knew the power of poetry from before, of course, and had been affected in different ways by a number of poets previously, especially by Les Murray, Pablo Neruda, Octavio Paz, and Yiannis Ritsos himself. Outstanding poets have the ability to provoke in equal measure both the intellect and the emotion. Howbeit, the closest to this immediate response of my heart which I experienced that night when I picked up Tasos Leivaditis to read for the very first time, was when I had some years earlier come across the numinous Rabindranath Tagore. Yet the sense here was, with the Bengali mystic and polymath, that he was speaking to ‘one and all’, like the universal soul he undoubtedly was. There was a ‘romanticism’ in the writings which could at times seem out of reach for the ‘ordinary’ person. And though Leivaditis’ themes are also manifestly universal as with all great poetry, he was able to informally transcend this distance and time which ordinarily stands between writer and reader, to look you squarely in the eye and sit down with you wherever you might be. Similarly to our own Bruce Dawe, he could with ease ‘localise’ the poem [or his short stories] cutting right to the heart of things.

“Or when sometimes I would eat with my friend Jeremiah in the cookhouse “who am I, Jeremiah?” I would ask him, I was eaten by the concern “if you treat I will tell you”, I would treat him, “you are a degenerate” he would say, silence from me, I would bow my head to pray and remember, a child, when mother and I would cry while reading “Two Orphans” and when we returned from the cemetery where we had left her all alone it was still raining, “and yet, mother”, I tell her, we suffered much together.”/ Similarly and when sometimes as we walk on the road, at night, a piece of music which is heard from our depths reminds us of another unbelievable life-/ When did we live it?” (T.L., The Manuscripts of Autumn, Music on the Road)

“It is not that you have lost your most beautiful dreams./ It is not that your best years have gone./ It is not that you saw, no, your last friends/ betray you or leave the battle./ This hole is horrible/ in the wall which you had painstakingly lifted, nights without sleep,/ destroying your hands and your years/ on the rocks – wall,/ that it might hide you from the relentless indifference of the void./ And now a small hole,/ almost invisible, from where enters silently and irrevocably/ all the cold of the great futility.” (T.L., Poetry 1958-1964, The Least Things)

“Spit on me/ hit me/ trample me/ I/ every night/ take revenge on you/ given/ returning home late/ inebriated/ humbled/ I lay down together/ with a nightingale.” (T.L., Poetry 1958-1964, Revenge)

“I never imagined that so many days/ make such a small life.” (T.L., The Blind Man with the Lantern, The Lies of the Calendar)

“And later I walked down the stairs with a sweet unspecified horror/ that I had lived so much without knowing it.” (T.L., Discovery, From the Confessions of Mathias X.)

“And during the nights the remorse like giant candleholders would keep me awake/ In this way I was purified in the morning.” (T.L., Small Book for Great Dreams, untitled)

“No, it is not a wing. It is his hand, as he tries to avoid the blows.” (T.L., Night Visitor, The Hand)

“Or other times, in the night, someone’s steps, faraway, would bathe us, suddenly, into their deep secret,/ then we understood, that all things would remain unknown to us,/ and that this would be our most beautiful testimony.” (T.L., Dark Act, untitled)

“Entry was prohibited except to those poor mad fellows who fantasised they were birds, ladders or trees - vaguely guessing that to enter into the mystery/ they would have to leave themselves outside.” (T.L., The Blind Man with the Lantern, Entry Is Prohibited)

“And my journey continued, I want to say that often I crossed the railroad lines entirely alone, where was I going? (I never found out) - the difficulties however began at night, I had to correspond, but with who? I had no one, so I too gave myself with passion over to my shoes, something which if you have not yet done, you have learnt nothing yet about the fate of humanity…” (T.L., The Blind Man with the Lantern, True Stories!)

“My shrug, his shrug; his smile, mine. Only the background is different on each side. (Stephen McInerney, Clear Creek)

I felt that I had met a ‘co-journeyman’

I desperately wanted more of this poet’s work. The next afternoon I saw my friend, the secretary, the one who had initially given me that first copy of Leivaditis’ book,[22] at the front offices of the seminary. She held out a bundle of books of varying size. I could only wish those slender volumes were Tasos’. She said I could have them for as long as I wanted. I remain amazed at providence even in this, how this story would in later years unfold to touch so many other aspects of my life. I felt that I had met a ‘co-journeyman’, someone who had experienced a large number of the self-same emotions to those I was living through at the time and who had [and was] successfully navigating through the ‘big storms’. Alienation from friends and community; despair at the corruption of once trusted institutions; melancholy upon the realisation that even beautiful things and meaningful encounters are temporal; and that love, like the writing of literature, can make some enormously serious demands of us. Yet, he could see the transfiguration of all of these realities which troubled him. He could point to a deeper manifestation of those things seen by the corporeal eye. To an alternate reading of ‘restored’ beauty. Recently, I came to understand this ‘repairing’ in terms of that sublime Japanese art called Kintsugi, putting broken pottery pieces back together with lacquer and gold. “It is built on the idea that in embracing flaws and imperfections, you can create an even stronger, more beautiful piece of art.”[23] The poet’s use of antithesis is “exemplary” and “consequential”.[24] For this reason, too, he can effortlessly slip into different personae, from laundry girls to kings, and express a broader and more integral compassion for his characters which come from all the social stratum of life. And not only as an expression through a particular genre, for if we must categorise him, it would be in the tradition of ‘magical realism’.[25] Later when I would fall under the marvellous spell of Marquez and Borges, I would understand more of Leivaditis’ own particular mastery of language, in the pure sense, of an outstanding skill.

“If I could someday explain that I, an insignificant, lost person, dreamt so much, but what did it matter, I only made sure to rest next to the night table, during the nights, what was left of the destruction, when they knocked, anywise, and I opened, I saw the child from the chandlery, who else, besides, could it have been and I wept from silent pride, that I was privileged, because the outcasts are like mothers, given that from their tight lipped pain was fed the unspeakable, I thought, then, a whole lot of things, till I built an entire life, outside the world, and when it would become dark, I would see in the mirror the candle standing alone, but there were times when I felt sorry for myself and I would open the window, as if there was a way they could still see me./ Night would fall, and I stood there, spellbound, before this vast apocryphal justice.” (T.L., Night Visitor, The Child from the Chandlery)

“What did they want, well, what had I done, my only crime was that I was never able to grow, always chased, where would you find time, and so I remained naïve, and embraced the cold steel of the bridge./ While from the deep, from afar, looking at me like a stranger, my own inmost life.” (T.L., Night Visitor, Guilt)

“So when they expel you, the reality becomes unbelievably distant as if imaginary, you do not even remember how you went down the ladder, how you crossed over the road, how you arrived at his point-/ like when you are driven, sometimes, by a music too much to bear by the hand.” (T.L., A Manual for Euthanasia, Route )

“From that moment (which you will all find yourselves one day), I understood that there is no other solution, I would walk about, then, during the nights and shake the letterboxes on the roads - they owe me an answer, anyhow it’s dishonest when you do not have to eat to buy pistols for confessions or how not to weep for him who has to wait for next September – and so, despite all of my precautions they managed it, while I was turning the corner they grabbed me and they put another in my place, “help” I shouted, my voice was heard from afar, “at least, my dead will recognise me” I thought and ran to the station/ and it was slowly-slowly becoming dark and the city beyond was being lost in an unfathomable darkness -/ and I was sick for God.” (T.L., The Blind Man with the Lantern, Scenes of the Station).

“During the nights my friends seek me out in the coffeehouses where they find a glass of cognac slowly-slowly emptying itself -/ but what could I have done having always existed/ on the other side of life.” (T.L., The Blind Man with the Lamp, A Question of Seating)

“But here, I finish. Time to leave. Just like one day you too will leave. And the ghosts of my life will now look out for me running through the night and the leaves will shiver and fall. Normally this is how autumn arrives. That’s why, I tell you, let us look at our lives with a little more compassion/ given that it was not ever real...” (T.L., Violets for a Season, untitled)

“Then they knocked on the door. I, naïve, as always, went and opened. And so a new grief entered the world.” (T.L., Violets for a Season, Mythology)

“And I also open my umbrella and I am in a beautiful park, dusk, while it rains and the birds run to hide/ in the sleep of children. The statues speak at night. And let the others say that I speak to myself.” (T.L., Small Book for Big Dreams, untitled)

“Accused, stand!” He stood. They said his name, year of birth, occupation, and later “you are sentenced to death”./ But he rejoiced, as he was hearing his name for the first time.” (T.L., Discovery, Notability)

“And to think I have always lived with this terrible dilemma - I mean to say, that the temptations are many, and often I would kneel to tie the laces of an empty shoe, which anyways it was what it would have asked.” (T.L., Discovery, The Details)

“And if I allowed them to humble me it was to hide other things/ darker still. Or does not the ladder in anywise take us where it wants!” (T.L., Discovery, Necessities)

“He really had been through death, but he had returned because he could not bear the solitude.” (Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude)

“The unicorn, because of its own anomaly, will pass unnoticed. Our eyes see what they are accustomed to seeing.” (Jorge Luis Borges, The Modesty of History)

What philosophers have called ‘the human condition’

Source: Personal Communications from maria leivaditis to M.G. Michael (M.G. Michael archives).

Reading Tasos Leivaditis helped me to better understand those novelists dealing with what philosophers have called ‘the human condition’, but it also shed more light on the discernment which Dostoevsky or Solzhenitsyn, for instance, revealed with their forensic insight into the permanent and universal values of life. "Literature is where I go to explore the highest and lowest places in human society and in the human spirit,” writes Salman Rushdie, “where I hope to find not absolute truth but the truth of the tale, of the imagination and of the heart.”[26] These sentiments on the power of various literatures to mirror our interior worlds have also been in recent times powerfully collated into a volume of eclectic texts by Richard Holloway, Between the Monster and the Saint: Reflections on the Human Condition (2008). Leivaditis’ own discerning perceptions of this human condition, the essentials of our existence, go much deeper than the purely reasoned without denying the reality which gives rise to them. As a philosopher-poet which most of our outstanding poets are anywise, he surveys our preconceptions and assumptions of what it means to be human in all of its ontological dimensions, to throw his sharp light on those permanent questions to do not only with our existence and being, but also with our becoming. Our poet would no doubt had agreed with this epigrammatic line from the American Quaker and author, and parenthetically the recipient of the Janet Heidinger Kafka Prize, Jessamyn West, who said: “[f]iction reveals truth that reality obscures.”

“Who are you, then, behind this face which each day changes,/ who are you behind the acts which you do during the day, behind the acts which you mull over during the night./ Innumerable faces inside you, each one demands to live killing the other – which is the true one? Which is that face/ that no mirror can give you?” (T.L., Poetry 1958-1964, Small Existential Parenthesis)

“And suddenly one morning, when we woke, with a woman next to us in the cold room of a hotel, we understood/ how little we had loved our neighbour.” (T.L., Small Book for Big Dreams, untitled)

“Insignificant things we have forgotten, but which one night we will remember/ and we will weep, while outside will be heard the whistle of a train/ for which departure or which return?” (T.L., Small Book for Big Dreams, untitled)

“He knelt and touched his forehead down on the floor. It was the difficult hour. And when he stood, his embarrassed face, which we all knew, had been left there, on the planks of wood, like an overturned, useless helmet./ The same he would return to his home now, without a face – like God.” (T.L., Night Visitor, The Defeated)

“A woman was sitting on a bench in the park, all alone,/ she was holding an umbrella, she had nowhere to go/ until she stood up and with slow, uncertain steps/ she ascended into the sky.” (T.L., Violets for a Season, Paradoxical Afternoons)

“Someday I would like to speak of this shadow which follows us in the fog – but it is forbidden for me to speak on the end of a story/ which never started to begin with.” (T.L., Violets for a Season, Small Thesis)

“What more do we people ask for, Bill? A world, he says,/ where they will not trample our dreams/ where they will not knock down our door step/ where we will be able to smile/ with a big laugh, spherical, wide/ here, like this Sun which is rising. Look, Bill.” (T.L., The Man with the Drum, untitled)

“Since then I have come to understand the truth of all the religions of the world: They struggle with the evil inside a human being (inside every human being). It is impossible to expel evil from the world in its entirety, but it is possible to constrict it within each person.” (Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago 1918–1956).

“What is hell? I maintain that it is the suffering of being unable to love.” (Fyodor Dostoevsky, The Brothers Karamazov)

It rests somewhere in-between literary realism and fantasy

One of the criticisms of magical realism has been that it is too idealistic or remains indifferent to the realities of the world. This could be because it is often wrongly conflated with fantasy, which it certainly is not. Magical realism is not separated from reality. Subversive texts and powerful anti-establishment sentiment is not missing in these authors, sometimes direct and other times subtle. Toni Morrison’s haunting [quite literally] Pulitzer Prize-winning Beloved (1987) which, it can be confidently argued, fits well into the magical realism genre, has passages in it which do not shy away from the brutal and are shockingly confrontative of the reality of the history she is describing. Leivaditis’ own visceral descriptions, for instance, of the inhumanity practised by one group in power over another persecuted political minority, is very clear. It is also not surrealism by any measure, and the difference between this and magical realism, is that the former is set in a dream-like world whilst the latter is situated in an entirely realistic setting. The genre itself rests somewhere in-between literary realism and fantasy.[27] These authors who have mastered this space have not disengaged with life. They have for a moment disrupted temporal reality and manipulated the ordinary into the extra-ordinary. The poetics of the genre are multilayered.[28] Haruki Murakami is perhaps the more well-known of the magical realists writing today. The Japanese author’s “Kafka on the Shore” (2002), which is a ‘search for the meaning of life’, received wide international attention, whilst in 2018 the Polish author Olga Nawoja Tokarczuk, the recipient of the Noble Prize for Literature, also dips heavily with her “narrative imagination” into the genre.[29]

magic realism, chiefly Latin-American narrative strategy that is characterized by the matter-of-fact inclusion of fantastic or mythical elements into seemingly realistic fiction. Although this strategy is known in the literature of many cultures in many ages, the term magic realism is a relatively recent designation, first applied in the 1940s by Cuban novelist Alejo Carpentier, who recognized this characteristic in much Latin-American literature.[30]

“And yet he must tonight before he dies/ to dig alone his own grave/ a hole/ into the hard frozen soil./ “That is what the order says.” (T.L., Battle on the Edge of the Night: The Chronicle of Makronisos)

“The bullets whistle at the moment/ a torn face/ the bullets nail the darkness/ someone lifts their jacket/ maybe he can hide/ no one wants to die/ the other one coils/ he becomes a small ball/ to be saved.” (T.L., Battle on the Edge of the Night: The Chronicle of Makronisos)

“Often, in the night, without realising it, I would get to another city, there was no one but an old man, who dreamt, once, of becoming a musician, and now, he sat, half-naked in the rain – with his coat he had covered on his knees an old, imaginary violin, “can you hear it?” he tells me, “yes, I tell him, I could always hear it”,/ while down the road the statue was narrating the true journey to the birds.” (T.L., Night Visitor, The Musician)

“When, at last, the time arrived to take me to the firing squad, they were all left speechless, - in the cell they did not find anyone but a dog curled up in the corner./ Which, of course, was not by chance they would usually call me a lazy dog.” (T.L., A Manual for Euthanasia, Ovid’s Metamorphoses)

“And in the house was that other house – there where Mother was still young and a flute was heard during the night, just like when they lead a blind man./ In this house we had also stayed forever, while as we were lighting the lamp, its light would only throw our shadows here on the floor.” (T.L., Manual for Euthanasia, Our Shadows)

“And when they buried me and heaped all the soil of the earth on me,/ the grief of a clumsy illusionist at the corner of the road was such/ that I came out of his hat.” (T.L., Discovery, The Resurrection of the Poor)

“As long as there's such a thing as time, everybody's damaged in the end, changed into something else. It always happens, sooner or later.” (Haruki Murakami, Kafka on the Shore)

“It's clear that the largest things are contained in the smallest. There can be no doubt about it. At this very moment, as I write, there's a planetary configuration on the table, the entire Cosmos if you like: a thermometer, a coin, an aluminum spoon and a porcelain cup. A key, a cell phone, a piece of paper and a pen. And one of my gray hairs, whose atoms preserve the memory of the origins of life, of the cosmic Catastrophe that gave the world its beginning.” (Olga Tokarczuk, Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead)

The poet as a ‘wandering wonderworker’

The poets themselves have given us many compelling definitions as to what “makes” a poet, and many of these would sit nicely here, with Robert Frost the first amongst equals: ‘a poem… a lump in the throat… homesickness… lovesickness.’ However, Erica Jong, the American novelist and poet has, with her own definition, summarised most and, inadvertently for me, highlighted each of Tasos Leivaditis’ charisms as a poet:

“What makes you a poet is a gift for language, an ability to see into the heart of things, and an ability to deal with important unconscious material. When all these things come together, you’re a poet. But there isn’t one little gimmick that makes you a poet. There isn’t any formula for it.”[31]

“The poetic thought of Leivaditis continually moves from the infinitesimally small towards the infinitely big, and conversely. From the ephemeral and momentary towards the everlasting and eternal. His apprehension is to bring together the All [to Olon], the infinite, similarly to the great romantics of the past century. That is why he has given himself over to a majestic struggle, despite the despair and the futility… only human spirituality, at its highest moment, as it clashes with fate, can give birth to “meanings” of immortality.”[32]

Source: https://www2.bfi.org.uk/news-opinion/news-bfi/features/five-visual-themes-wings-desire-immortal-film-about-watching

There is an additional element that I would add here when one explores Tasos’ ‘ontology’ of the poet’s spirit who it is assumed is for the most part hidden. It is their being and / or becoming into the craft as a ‘wandering wonderworker’. The poet is capable of supernatural actions because they see and observe in the natural order of things what others cannot. Not everyone can be a poet, not because they are incapable, but rather because they are not willing to empty themselves of the weight of the world so that they might become receptive vessels of revelation. Tasos’ poets, indeed, can do and can reveal wondrous things, but they are humble, and poverty stricken, and walk about us anonymously and destitute. They can be sometimes recognised by the marginalised [and even the dead], perhaps something akin to Wim Wenders’ angels in his classic “Wings of Desire” where only other angels and little children can see supernatural beings.[33] Leivaditis is not saying that we should take this literally, any more than he is saying that a poet can fly on the wing of a bird; rather, he is stressing a necessary spiritual disposition, a kenosis of sorts. He was no doubt familiar with the great hymn of the kenosis [“the self-emptying”] of Christ as recorded by Saint Paul in his epistle to the Philippians (2:7). Is there an argument to be made of a ‘kenotic imitation’ as the ultimate sign and goal for poets in order that they might receive their special charisms?

“Poor stowaways on the wings of birds/ the moment they fall wounded.” (T.L., The Manuscripts of Autumn, Poets)

“Poor who pass on the streets, hiding in their broad torn coats some poet, who was denied by fate or he was deceived by circumstances/ but who every so often gives them their most beautiful tears.” (T.L., Violets for as Season, Poets Move About us)

“Suspicious wonderworkers who shoot at words - and become birds.” (T.L., Violets for a Season, Poets)

“Everyone has returned. Only the poets have forever stayed over there.” (T.L., Violets for a Season, Unspecified Signs)

“…until the moon leaned on a hill, bloody - like the poet on this obsolete alphabet.” (T.L., Discovery, Family Gathering)

“At every moment we are in danger, but no one – the photographs on the wall, the furniture, the memories, the key, stand there, unable to help you – like the words/ when the poem ends.” (T.L., Discovery, The Words) 91

“An entire life, not even one day without a verse, or, at least/ some poetical inclination. Like the moribund/ who speak constantly and give blessings and orders,/ who make oral wills and even share non-existent/ inheritances – knowing that when they become silent/ they would have died.” (T.L., Poetry, 1958-1964, Poetry)

“An old sentimental candle was burning on the table/ my worn out furniture had taught me patience/ only one thing, my God – I did not live: having to take care of/ so many leaves during spring.” (T.L., The Manuscripts of Autumn, The Poet’s Complaint)

“He was passing a deserted road, night, when he heard tears. An infant was at a door. He stood, later he made to leave, but stood again. He lifted the child in his hands and departed./ The lamp on the table was burning. He did not lower the flame, as he would normally do, when he was undressing. He opened his shirt and looked at the small, female breast which was sprouting on his chest./ And he smiled pensively, as he put the nipple into the mouth of the child.” (T.L., Night Visitor, The Poet)

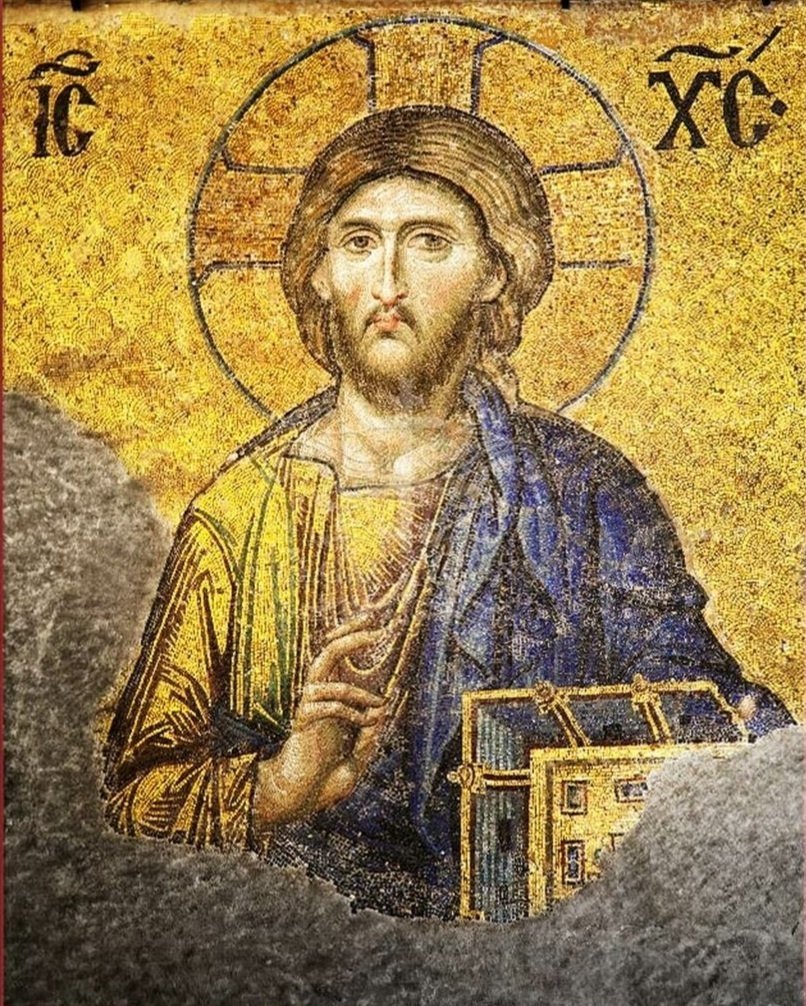

Without trying to reinterpret the poet’s Christology

Source: https://legacyicons.com/christ-pantocrator-hagia-sophia-icon-x114/

The person of Christ both in his humanity and as a transcendent figure, will often appear in Tasos Leivaditis’ work, more so in what is considered his “Third Period” (1979-1987). It was during this time that The Blind Man with the Lantern (1983) was published which included those enchanting (12) Conversations all beginning with the supplication “Lord” [Kyrie]. These are immediately followed by four additional pieces collectively titled, The brother Jesus. Here it is appropriate to mention only months before his death, he would say in an interview: “Eimai thriskevomenos”.[34] That is, “I am religious”.[35] Certainly, without trying to reinterpret the poet’s Christology, he does distinguish between God whom he has a “sickness” for and searches after tirelessly and Jesus the compassionate “fellow-traveller”. In fact, Tasos opens the collection Night Visitor (1972) with an illuminating quote from the gospels where Christ challenges one of his disciples: “Don’t you know me, Philip, even after I have been among you for such a long time?” (Jn 14:9). Nikos Kazantzakis searched for God, too, for all of his life, for all that he ultimately could not come to terms with the ‘Christ of the Church’, yet he did not abandon his search.[52] If Kazantzakis was what we might call a ‘process theologian’ as Dombrowski argues, in Gospel terms Leivaditis has a Marcan conception of the Christ where the emphasis is in Jesus’ humanity rather than in his divinity. This gradual shift from the earlier more politically infused writing to his more religiously inspired reflections on the “meaningfulness” of life [and here I’m thinking of Viktor Frankl] did alienate him from some, but never in the same way as say, the infamous schism between Sartre and Camus. Besides, how is it ever possible to pull apart the political and religious elements from the consciousness of a creator who is civically engaged with the world. Like the two personalities fighting, engaging in a metaphysical battle, on the inside of the poet himself, something which Yiannis Kouvaras has highlighted in our poet’s persona as “identity and otherness”. Students of Ernest Hemingway might be similarly surprised when they first hear of the great American author’s uneasy flirtations with Catholicism.[36] The ‘machismo’ Hemingway would often grapple with the question of sin and the concept of redemption, which has been brilliantly underplayed, for instance, in The Old Man and the Sea (1952). For the moment, the most notable example I can offer here, are the prophets of the Old Testament as an archetypal embodiment of this meld where politics and religion are very much inseparable.

“…I believe in the tentative unrehearsed steps of the humble/ and in Christ who cuts through History...” (T.L., The Blind Man with the Lantern, Brother Jesus)

“Lord, you are our daily bread, our great nostalgia to return – where?/ You are the womb who will give birth to us after our death./ Amen.” (T.L., The Blind Man with the Lantern, Conversations 3)

[The birth of speech] “Lord, you are the mighty infinity we breathe, the never-ending road we go./ You are the indescribable silence we hear inside us and we talk – that we do not die of fright.” (T.L., The Blind Man with the Lantern, Conversations 7)

“Lord, my sin is to be found in that I wanted to resolve your riddle, to enter into your mystery/ and so I was led astray the madman – in that I am your great secret.” (T.L., The Blind man with the Lantern, Conversations 10)

“For aeons now I knock on the wall, but no one answers. Yet I know that behind the wall is God. Because only He does not answer.” (T.L., Night Visitor, untitled)

“Whom will I love? To whom will I confess? Only God can boast that he heard me complain…” (T.L., Night Visitor, Ambush)

“Consumed and exhausted Jesus stood near the tomb. “Lazarus come out” he called. They all waited. And the poor dead man who felt that here in his tomb the fate of the world was being played out, what could he do? The earth was lost,/ how could he leave a whole heaven without resurrection…” (T.L., Manual for Euthanasia, God Needs Our Help)

“Comrade are you here/ I do not see you in the dark/ and this corporal of the change of guard/ delays/ what time could it be/ I am cold.” (T.L., Battle on the Edge of the Night: The Chronicle of Makronisos)

“A piece of pencil/ do you know what it means/ when someone is cold./ When you do not want to die/ do you know what it means/ life.” (T.L., Battle on the Edge of the Night: The Chronicle of Makronisos)

“To see and accept the boundaries of the human mind without vain rebellion, and in these severe limitations to work ceaselessly without protest - this is where man’s first duty lies.” (Nikos Kazantzakis, The Saviours of God)

“It's silly not to hope. It's a sin he thought.” (Ernest Hemingway, The Old Man and the Sea)

As the dear pants for streams of water, / so my soul pants for you, my God. / My soul thirsts for God, for the living God. When can I go and meet with God? (Ps. 42:1-2)

Not all gloom and despair, life is rich with experiences and surprises

Or… alongside the “biblical rains” there are the “ladders”.

“Tasos Leivaditis makes us live not only in one but in many worlds, discrete, yet at the same time connected between themselves. Similarly to how the great painters up to and after the Renaissance, who in addition created another world above us, and one below us, but which are enlivened by one single power. Or like the the three world of Dante, Hell, Purgatory, Heaven which are moved by one only. Power: L’amor che muove il sole e l’altre stelle.”[37] (Titus Patrikios)

Source: Personal Communications from maria leivaditis to M.G. Michael (M.G. Michael archives).

A new reader to the poet might too quickly get the impression that there is too much despondency, too much introspection, and an unhealthy preoccupation with mortality. That would be plainly wrong. It is not all gloom and despair. Life is abounding with far-reaching experiences and astonishing surprises in Tasos Leivaditis’ writing- and in the salutation to the endurance of the human spirit, to overcome and not to yield. Even before the darkest obstacles, there rests the potential for metamorphosis; not in the sense of a change of the form or nature of a person, and into a completely different being, but rather in the transformation of our perception and hence, our responses to those things which might compress us. We could call this an awakening to another reality, or meaningfulness. To use the well-known Protestant phrase of spiritual regeneration: to be “born again”. Whatever avenue of literary criticism one takes with our poet, whether the emphasis is put on the poetics or the hermeneutics, the essential theses of his work remain the same. Irony and antithesis, as I have already alluded to, together with a literal treasury of metaphors and allusions, would be the elemental first step of discovery when one enters into Tasos Leivaditis’ ‘autumnal’ atmosphere. If there are contradictions, and certainly there are, because this is life, and the expression of anything else but that, would wholly lack in integrity. In a recent essay where I similarly investigated the mystical elements in the writings of another poet in my home country and short story writer, David Brooks, who in his sensitivity, observations, and mode of expression, does remind me of Leivaditis, I used the orthodox monastic expression of “joyful-sorrow” to describe the awareness of this existential tension.[38] We are moved and saved by honesty, with tough love or bitter medicine. And so, alongside the “biblical rains” are the “ladders” and the “fair hour”.

“Do you remember the nights? To make you laugh I would walk on the lampshade./ “How is that done?” you asked. But it was so simple/ because you loved me.” (T.L., Discovery, To a Woman)

“Oh twilight, fair hour, when even on the humblest things/ you give a meaning before the night comes.” (T.L., The Manuscripts of Autumn, Hour of the Twilight)

“Everyday something ends, in this way we gradually become accustomed to the great finality/ we see a hat on the grass, a piano next to the sea, a woman in the rain -/ do you remember the sanatorium in the faraway suburb and our correspondence from our neighbouring rooms/ later the departure and a simple greeting without a fable./ And afterwards came the night and the stars were the last sign that/ we had been in love…” (T.L., The Manuscripts of Autumn, Adventure)

“Now the years have passed and I who loved all the joys of the world/ the time has come for me to deny them - the days pass quickly/ and at night this unnamed person appears by the ladder “what do you want?” I asked frightened “my share he would answer…” (T.L., The Manuscripts of Autumn, The Unnamed Person)

“Despite all my misfortunes the reputation of which would have been enough to make me glorious I never once lost my hope. And what is more: every morning I would dress and would triumphantly come out of the house.” (T.L., The Manuscripts of Autumn, The Treasure)

“A broad, cool smile ran down your naked body,/ like a paschal branch, early, in spring/ all of you was dripping in pleasure, our love cries/ exploding in the sky like big bridges/ upon which would pass the centuries – ah, that you would be born,/ and I to meet you/ that is why the world was made. And our love was the vast ladder which I climbed/ above time and God and eternity/ up to your incomparable, mortal lips.” (T.L., Poetry, 1958-1964, A Woman)

“And mother, I remember, “you sit around all day”, she would say with longing, “I am not sitting mother”, I would say back to her. / And truly, from the near cemetery a gentle aroma would arrive- as if mortality had some meaning.” (T.L., Manual for Euthanasia, Indistinguishable Tasks)

“An indefinite great promise, as it will always happen/ in old room chambers/ or a gentle gesture as you pin a tuberose/ on the breast of a woman/ who never existed.” (T.L., Manual for Euthanasia, Gestures)

“…Biblical rains on the inside of me which I shared to the itinerant umbrella salesmen” (T.L., The Blind Man with the Lantern, Excerpt of a Future Poem)

“I then open my window and unwittingly I smile. God, for yet another time, won me over with his new day.” (T.L., The Blind Man with the Lantern, Ancient Controversy)

Above all the poet found refuge in his family and loved music [or some further notes for those contemplating advanced studies on the poet]

source: H lexi , Afierwma tasos leivaditis, November-December ‘95 Vol. 130, p. 775 [the poet with his wife maria and daughter vaso, during his exile on ai-strati, 1951].

Leivaditis enjoyed spending time with a close knit group of friends; he treasured solitude and quiet spaces; and avoided unnecessary confrontation. Above all he loved being at home in the company of his beloved family where he would also find refuge from the “daily bombardments” of life.[39] Music, which is also prominent throughout his writing, was an essential part of his life, particularly classical music. Maria told me he would listen to Chopin and the Russian composers. When it came to philosophy he was inclined towards the pessimism of Schopenhauer, they certainly shared the belief of the vitalness of music and understood well the heaviness of depression. He was as expected, a voracious reader with a treasury of literary references and allusions to be discovered in his publications by the keen reader: Rimbaud, Rilke, Chekov, Kafka, Dostoevsky, Lorca, and others. The collection Man with the Drum (1979) is a revealing example of the literary and geo-political spaces which our poet inhabited: from Moscow…, to Guatemala…, to Hiroshima…, to Arizona. What might surprise, however, is his admiration for Jack Kerouac, one of the founding fathers of the Beat Generation, and Tasos’ favourite American writer.[40] Kerouac lived on the edge of society; wrote his most successful book, On the Road (1957), as a ‘wandering poet’ within the concentrated surrounds of music and poetry; he dove deep into the tensions of life; and was not one for the trappings of ‘high society’. What is more, he did not dismiss religion as a potential source of meaningfulness, something which is often treated too lightly by Kerouac reviewers, whether through his agitated connection to Catholicism or his later more determined investigations into Buddhism.[41] There are moments too, when I read the famously ‘iconoclastic survivalist’ German-American poet Charles Bukowski, or listen to his poetry online, when I am struck with certain imaginative similarities with Leivaditis himself.[42] It is no coincidence Tasos and the authors I have mentioned fit faultlessly inside Charles Baudelaire’s pithy statement: “[a]lways be a poet, even in prose.”

“The bell of the front door was ringing persistently, I took my time to open, enjoying as I always did the suspense. When I opened a young man was standing outside. “You are Arthur Rimbaud from Charleville, I said – how may I help you?” “We are both in danger” he said.” (T.L., The Manuscripts of Autumn, The Hydrangeas)

“Tonight the wooden crosses we made them into a giant scaffold/ on which the elevated workers with songs and hammers build/ a new horizon/ city, key city, which you unlock all the despairing hands/ and all the jasmine, it is of you which Lorca sang.” (T.L., The Man with the Drum, from Guatemala)

“One day I will find the right words, and they will be simple.” (Jack Kerouac, The Dharma Bums)

“there is enough treachery, hatred violence absurdity, in the average/ human being to supply any given army on any given day…” (Charles Bukowski, The Genius of the Crowd)

I have done nothing more here other than to have made a small mark

Source: a copy of one of tasos leivaditis’ poems handwritten by maria leivaditis. one of her favourite poems. Personal Communications from maria leivaditis to M.G. Michael (M.G. michael archives).

I have done nothing more here other than to have made a small mark. All the same for me at least, it was a necessary testimony of thanks both to the poet, whose spirit stood by my side to contain me, at a time when Scripture was too difficult and distant, and to Maria, who offered me support and friendship during some of my darkest hours. That some historical contingencies made it all but impossible for me to fulfil the promise I had made to her, to translate Tasos, will remain an enduring hurt. Yet, as I have elsewhere referenced, these translations have been done by another, and done well. Below the reference to the Bible is moving for me, for in all likelihood this could be the very same which Maria herself used in our exchanges.

“Typically on my table I have a heavy leather bound Bible which is opened. I think in there is a hint on the great secret which God, in his magnanimity, has kept from us lest he add even more afflictions onto us. But one day the stories of the earth will come to a close and I, too, must have my word. So when the photographer came “for what purpose?” I tell him. And later as I was watching him from the window I saw that he went and sat down sad by the seashore and begun to throw little stones into the vast sea.” (T.L., The Manuscripts of Autumn, The Photographer)

Postscript, some additional pieces of information

This self-inflicted ‘wound’ would pain me by degrees

Caption: tasos leivaditis. source: copy of photograph sent by maria leivaditis to m.g. michael (M.G. Michael archives).

Unbelievable as it now seems, one of the most difficult things I have had to do was to stop reading the poet. This self-inflicted ‘wound’ would pain me by degrees for close to a decade. The reason not hard to understand and I’m sure something most creators have done battle with. Which is, the struggle and importance of finding your own voice, away from your major influences and mentors. Seamus Heaney has called this finding ‘the way’. Even today, for example, it can still be difficult to distinguish between the works of some of our greatest painters and their apprentices. But this battle needs to be entered into and acknowledged. Though there is “no new thing under the sun” (Eccl. 1:9), we can still bring or add something of our identifiable voice to the story, that is, to brush the picture with our own unique perspectives and experience of things. I had read Tasos Leivaditis so persistently and during some of the most impressionable periods of my life, that his words and his ‘stream of consciousness’ were becoming part of my everyday thinking and writing. My dearest Maria would sometimes tease me. She would say I had started to remind her of her Tasos. To this day these words can still flood my eyes with tears and they never fail to encourage me when rejection of any sort might come my way. Needless to say, these were terms of endearment. She had a beautiful heart and knew how to lift my spirits. Some time in my mid-thirties when I had begun to discover and to experiment with my own voice and the “very short story” [micro-story] format, I emerged from this enforced ‘separation’ with some embarrassing juvenilia in tow for I was your classic definition of the late developer. It was only then that I was able to once again freely engage with the poet. He will always remain one of my lasting inspirations. I came across the Hispanic authors later when I started to connect the dots. My very first introduction to the ‘magical-realist’ genre was in all likelihood Kafka’s, “The Metamorphosis” (Die Verwandlung, 1915).

"He lay on his armour-like back, and if he lifted his head a little he could see his brown belly, slightly domed and divided by arches into stiff sections." (Franz Kafka, The Metamorphosis)

“…an irrational nostalgia to again see my father, but the years had passed, and innocence now staggered, like an angel suffering from his wings,/ “do not betray me” he said, and then how he opened his coat I saw the demon, which had eaten all of his body, and his head was now balanced on the hand of the anchorite,/ who was praying in the desert.” (T.L., Night Visitor, Metamorphosis)

“Fisai”, George Tsagaris, Vasilis Papakonstantinou… and Helen Constanti!

In 1993 an album was released with poetry from Tasos Leivaditis, orchestrated by the composer George Tsagaris, with lead vocals from the instantly recognisable “Greek rocker” Vasilis Papkonstantinou.[43] Tasos’ poetry was introduced to a new generation of younger readers who rushed to discover his books. The title “Fisai” is taken from Leivaditis’ “It is Blowing on the Crossroads of the World” (1953). The anthology which received first prize for poetry at the World Youth Festival in Warsaw, was responsible for the poet being hauled to court on account of its universal message of peace. This was at a time as Yiannis Kouvaras writes, when we were “in the heart of that season of the cold war.”[44] The poet was supported by large groups of people and literary figures throughout his new ordeal. His ethos and inspired defence touched the hearts of many and moved the court to pronounce his innocence.[45] Who would have known here, too, with the album, there would be further connection to my own “crossroads” with the poet. This time not through Maria. It was to be through Helen Constanti, the godmother of my eldest child. Knowing my love for Tasos, she would do everything in her power to bring me into contact with him, though unaware herself that he had already passed away. One of her letters to the publishing houses addressed to the poet, would ultimately find its way to Maria who wrote back to Helen. They established communication and became great friends, in due course meeting and spending time together in Athens.[46] So here was the link to my own friendship with Maria. Why, then, this reference to the album? Helen, a beautiful singer, a mezzo soprano, recorded a number of the songs from “Fisai” on an old cassette recorder in her home to surprise Maria who then forwarded the tape to George Tsagaris! He responded with a very touching reply to Helen. She was then in her early 60s and had not sung in decades owing to devastating losses in her own life. It is no wonder then, that this recording outside its evident artistic pedigree, is especially precious to me.

From George Tsagaris to Helen Constanti: (30.10.1996)

SOURCE:: helen constanti (M.G. Michael archives)

“Friend Helen,

Your love for Tasos gives me the right to feel you as my friend even though we have not met. I was greatly moved, listening to your voice singing the music of “Fisai” which I had the delight to write inspired by our incomparable Tasos. Ongoing creative joy from my heart.

George Tsagaris”

The Greek word itself is resonant with deeper meaning

“It was the first time a poet [T.L.] had recited poetry from his anthology before an audience which would come to listen to popular music.” (Mikis Theodorakis)

source: H lexi , Afierwma tasos leivaditis, November-December ‘95 Vol. 130, p. 718. [Tasos leivaditis with irene papas,, mikis theodorakis and alekos alexandrakis

One evening Maria called only hours before a remembrance memorial which had been planned in Athens to celebrate the life and work of the poet. Music was to be an important part of the program. Tasos Leivaditis’ verse is behind a number of Modern Greece’s iconic songs.[47] This includes the classic: Drapetsona, a hymn to the working class famously interpreted by Grigoris Bithikotsis.[48] Maria knew I was an admirer of Mikis Theodorakis so she had arranged for the legendary composer to pick her up for the event around the time we spoke. Theodorakis, who became an international household name with Zorba the Greek (1964), was one of the main presenters.[49] They were great friends and Mikis, similarly to Yiannis Ritsos, loved the poet. Certainly, their shared political leanings and experiences of political exile, solidified these friendships even further. During our conversation Maria paused for a moment and said someone wanted to say: “Hullo”. The familiar voice over the phone, to my shock for it was the last thing I could have expected, belonged to Theodorakis. The reason I share this special memory is for the question I asked this towering Greek figure: “what had especially endeared him to the poet?” In a few simple words which have remained imprinted in my mind and using the hypocorism favoured by Tasos closest friends, he said: “O Tasoulis… h semnotita tou.” That is, his modesty. The Greek word itself is resonant with deeper meaning and it also carries across the ideas of sobriety and humility. Indeed, a wonderful legacy to aspire. It would have pleased the poet.

“Take our geranium, take our wreath/ In Drapetsona we don’t have soul anymore/ Hold my hand and let’s go my star/ We will survive even if we are poor.”[50]

By M.G. Michael © 2021

YouTube Documentary Sources

[1] For an overview of TL’s timeline see: Diavazw, Vol. 228, (Dec., 1989), 20-24; for a bibliography of TL’s publications including a very helpful list of critical studies, reviews, and methodologies employed to study the narrative structures and symbologies of the poet’s work, see: H Poetike Mythologia Tou Tasou Leivaditi, Apostolos Benatsis, (Epikairotita: Athens, 1991), 359-380.

[2] https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/yannis-ritsos

[3] https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/les-murray

[4] Diavazw, op. cit., 61.

[5] Curiously in the copy of Diavazw which Maria herself had sent me, the poet’s name in the biographical outline is written as Panteleimon-Anastasios, with Anastasios being the second name. In fact, in another place in that same paragraph, Anastasios is mentioned directly as “his second name”. What should be noted, however, is that Maria in my own copy had with blue pen rubbed out “Panteleimon” and also the reference to “second name”. The implication being, this was incorrect, that Anastasios was the first name.

[6] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Internal_exile_in_Greece; see also https://www.amazon.com/Becoming-Subject-Political-Prisoners-1945-1950/dp/157181308X

[7] https://www.tellerreport.com/life/--%22hellhole%22-makronissos--the-island-of-the-exiled-.S1GlXvobN.html

[8] Alexandra Boufea in her essay discussing Leivaditis’ search for God, H Anazitisi tou Theou sto Ergo tou Tasou Leivaditi, confirms these dates where perspectival transferences in the poet’s work can be noted: 1st Period (1952-1965); 2nd Period (1966-1978); 3rd Period (1979—1987): Diavazw, op. cit., 67-78.

[9] Maria would tell me Tasos would still bring her flowers late in life, enjoyed singing, and that he was certainly not without a sense of humour! This should not surprise. I don’t think it possible to engage in the world of magical realism without a keen sense of the bizarre and a strong insight into the power of irony. After all, the element of ‘surprise’ [which is prominent in TL’s writing] is a vital component of humour.

[10] The elegiac yet beautiful, The Manuscripts of Autumn (1990), was incredibly discovered as an unpublished MS in the drawer of the poet’s desk not long after his death. It was consequently published by Ekdoseis Kedros and copyrighted by Maria, and their only child, Vaso Leivaditou-Hala.

[11] My correspondence with Maria revealed her as a deeply sensitive soul who was ideally suited to be the poet’s life partner, she expressed very similar concerns about the manifest inequalities in the world and a vocabulary reminiscent of Tasos’ own ethos. She had a strong faith and would especially emphasise divine providence during our telephone talks. Two disclosures in particular which she shared with me about the poet one night so impressed me that I will often return to them. They are indicative for any student of Tasos Leivaditis’ to note. The first, when passing by a church he would invariably enter to light a candle, and the second, that inside his coat she would oftentimes find little paper icons pinned to the lining.

[12] Apostolos Benatsis, op. cit., 83-87.

[13] Diavazw, op. cit., 44.

[14] https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/abs/cambridge-companion-to-hemingway/hemingway-and-politics/6037C33BC03E1CCE09205E527180AC18

[15] H Lexi, Afierwma Tasos Leivaditis, November-December ’95 Vol. 130, 777.

[16] Selections of the poet’s work had been translated earlier into English by the Greek-American poet Nikos Spanias and by the well-known translator Kimon Friar, as I was to later find out: https://thereaderwiki.com/en/Tassos_Livaditis.

[17] In the intervening years I had probably translated close to four hundred pieces, including almost in their entirety Night Visitor, The Blind Man with the Lantern, and The Manuscripts of Autumn. Unfortunately, the greater part of this labour of love no longer exists. These present translations are my second effort [I did not consult with what remains of my earlier efforts until this essay was completed and am pleased to say I found no major deviations].

[18] For a taste of some of these authors, Tasos Leivaditis included, see: https://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/dedalus-book-of-modern-greek-fantasy-david-connolly/1103715728

[19] I approach translating with a great deal of joy, but also with large amounts of “fear and trembling”. It is for my enjoyment and to share this discovery directly with the authors themselves. I was delighted when Les [with whom I corresponded for almost twenty years and dearly loved] suggested we publish my translations of his work. Now, Les, was also quite the linguist so he must have somehow found out I had done a half decent job, because he was professional to a fault and would never make such requests lightly. I regret not agreeing to this, for as I explained, this needed a master translator [someone let’s say with the natural abilities of Vrasidas Karalis who did a phenomenal job with Patrick White], and I would not risk representing his work in a lesser light. I would feel more confident now, but still not without some degree of trepidation.

[20] I was invited by the editors of Southerly some time ago to contribute to a special volume dedicated to David Brooks. It was a much deserved festschrift not only honouring his services as a long time editor of the highly rated journal, but also his wonderful writing which has received international acclaim. In my essay I explain the reasons for my attraction to DB’s poetry and why I was compelled to translate him. A small number of these translations are in David’s possession. https://dgbrooks.wordpress.com/2019/04/14/new-and-forthcoming/

[21] https://newrepublic.com/article/62610/the-art-translation

[22] The Blind Man with the Lantern (1983).

[23] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kintsugi

[24] Apostolos Benatsis, op. cit. 176-189, 272-277.

[25] https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/what-we-talk-about-when-we-talk-about-magical-realism/

[26] Quoted in Observer (London, February 19, 1989).

[27] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Magic_realism

[28] I have not been able to access Vagia Kalfa’s MPhil. (2015) study on the poetics of Leivaditis but reading her abstract where she references the poet’s subtle yet evident shift from realism to symbolism and going by the title alone, “The poetics of Tasos Leivaditis: from extroversion to introversion”, definitely warrants a reference here: https://etheses.bham.ac.uk/id/eprint/6483/

[29] https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/2018/tokarczuk/facts/

[30] https://www.britannica.com/art/literature

[31] Conversations with Erica Jong (ed. Charollete Templin), (University Press of Mississippi: USA, 2002), 22.

[32]H Lexi, Manolis Pratikakis, op. cit., 795.

[33] https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5325/jasiapacipopcult.6.1.0109

[34] Diavazw, op. cit., 67.

[35] This is a huge topic and I did not want to press Maria further on the question. From what I could discern both from our conversations and correspondence, the poet possessed an Eastern Orthodox phronema without ever completely abandoning his own leftist ideals. Critics are divided as to the extent of Tasos’ religiosity. Whether it was just that, a “strong religious feeling or belief”, or something deeper and established. Julian Barnes, the winner of the Man Booker Prize in 2011 for The Sense of an Ending, was famously quoted as saying: “I don’t believe in God, but I miss him.” We can be certain of this at least, Tasos Leivaditis did ‘miss God’ and this he himself told us many times. The question then: what exactly did he mean by the referent “Theos”. This would make a fascinating long study, tantalising I would say, the material and some of the initial groundwork is certainly there.

[36] https://angelusnews.com/arts-culture/the-troubled-catholicism-of-ernest-hemingway/

[37] H Lexi, op. cit., 715.

[38] https://www.austlit.edu.au/austlit/page/15864368

[39] H Lexi, op. cit., 832-835.

[40] ibid., 835.

[41] https://headstuff.org/culture/literature/spirituality-in-the-writing-of-jack-kerouac/

[42] There are a number of examples I could suggest here, but begin with Bukowski’s memorable: “The Genius of the Crowd” (1966).

[43] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rs9jvNqsPks

[44] Diavazw, op. cit., 21

[45] ibid., 21f.

[46] Helen Constanti would later also correspond and forge a lovely friendship with Vaso, the only child of Maria and Tasos.

[47] https://www.amazon.com/Mikis-Theodorakis-Lyrika-Poetry-Livaditis/dp/B004JKLSLW/ref=sr_1_1?keywords=Tasos+Livaditis+CD&qid=1637970109&s=music&sr=1-1

[48] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grigoris_Bithikotsis

[49] Theodorakis affectionately recalls Tasos Leivaditis’ introduction into Greek popular music, the ‘songs of the people’ and describes how the Drapetsona song came about, see: H Lexi, op. cit., 719.

[50] https://lyricstranslate.com/en/node/84296#songtranslation

[51] H Lexi, Afierwma Tasos Leivaditis, November-December ’95 Vol. 130, 708.

[52] Kazantzakis and God, Daniel A. Dombrowski, (SUNY Press: NY, 1997).

[53] See Stelios-Petros Halas’ visually rich and historically significant archive: https://stepeha.wixsite.com/tasosleivaditis/blank