On the wickedness of typecasting

/"And Nathanael said to him, "Can anything good come out of Nazareth?" Philip said to him, "Come and see" (John 1:46).

Gioacchino Assereto Christ and the Woman taken in Adultery

Has there ever been a terrible wickedness where typecasting has not been involved? Is not typecasting a precursor to all forms of prejudice? Genocides and persecutions and other atrocities are they not founded in the typecasting of the other? Still closer to home, bullying and the mistreatment of our neighbours are they too not the result of typecasting. What does this word mean which we have come to chiefly connect with actors who have become identified with a particular role. To typecast means “to identify as belonging to a certain group.” It is as dangerous and can be as entirely misleading as is the practice of data mining to build a picture of an individual. It is no accident that great teachers do not typecast their students. The surest way to keep a bad habit or behaviour alive in a student is to ‘typecast’ him or her as lazy, or incompetent, or as obstinate. That is, to create the mistaken and horrible idea in their minds that they are without any value and so convincing them that there is “no way out.”

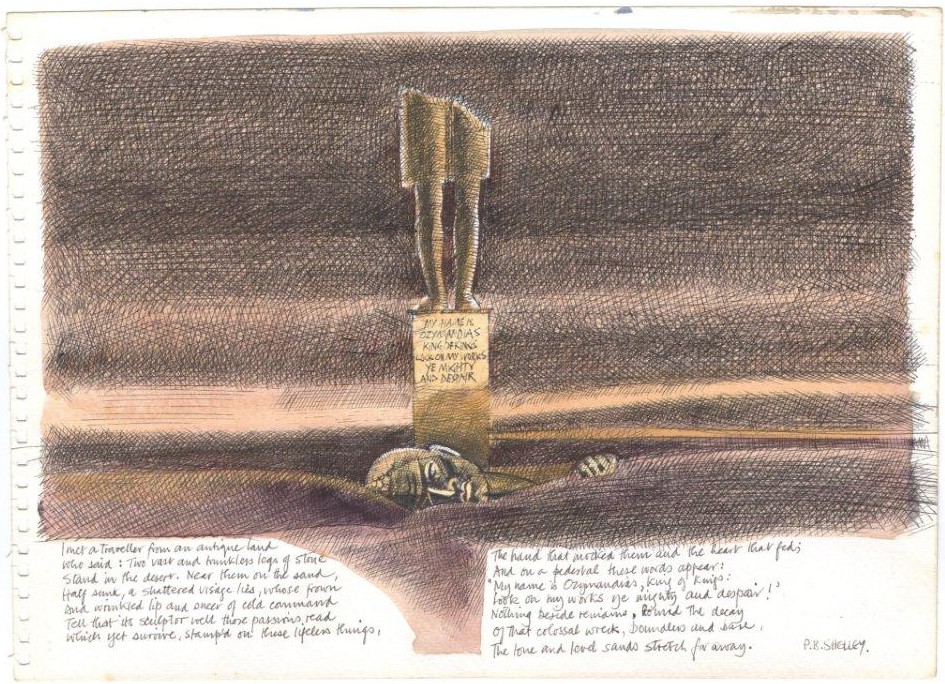

We can also unconsciously (and sometimes not so accidentally) typecast our partners and children or even our best friends. This can only serve to diminish the spirit of the other, and to limit their creativity and inspiration. Ultimately, and worst of all, it is to deny to a creature of God their real worth and true potential. In some instances the typecasting of individuals has led to the infliction of unbearable pain and resignation from all pleasurable endeavours of life, even to the extent of self-harm. To contrast, in the Gospel there are numerous instances each one more striking than the next, where Jesus Christ gives the abundance of hope and releases a dynamic force in the lives of both the sick and the marginalized. Many are familiar with the famous account of “the woman taken in adultery” (Jn. 8:1-11). There is a confrontation between the Nazarene and the crowd who want the woman to be stoned. The crowd is shamed by Jesus and quickly disperses, he does not typecast the woman and so she lives. He does not identify the hapless creature to her transgression. He sees into the future and discerns her undisclosed potential. Yet he does not patronize her, the bar is set high and there is something to aim for: "go, and sin no more”.

By our own attitudes and biases we can force those near us to remain in a deadly rut. We can convince them that they are not capable of anything greater than their current state or that they are slaves to their weaknesses or addictions. On the universal scale tyrants and dictators have typecast entire races of people based on colour and creed in their demonic bid to either obliterate or to control generations of men and women. Typecasting has also contributed to crimes of inequality and to a whole range of discrimination. In the Lotus Sutra the Buddha preached against ‘typecasting’ when he spoke against the caste system, an unjust social structure already established in his time.

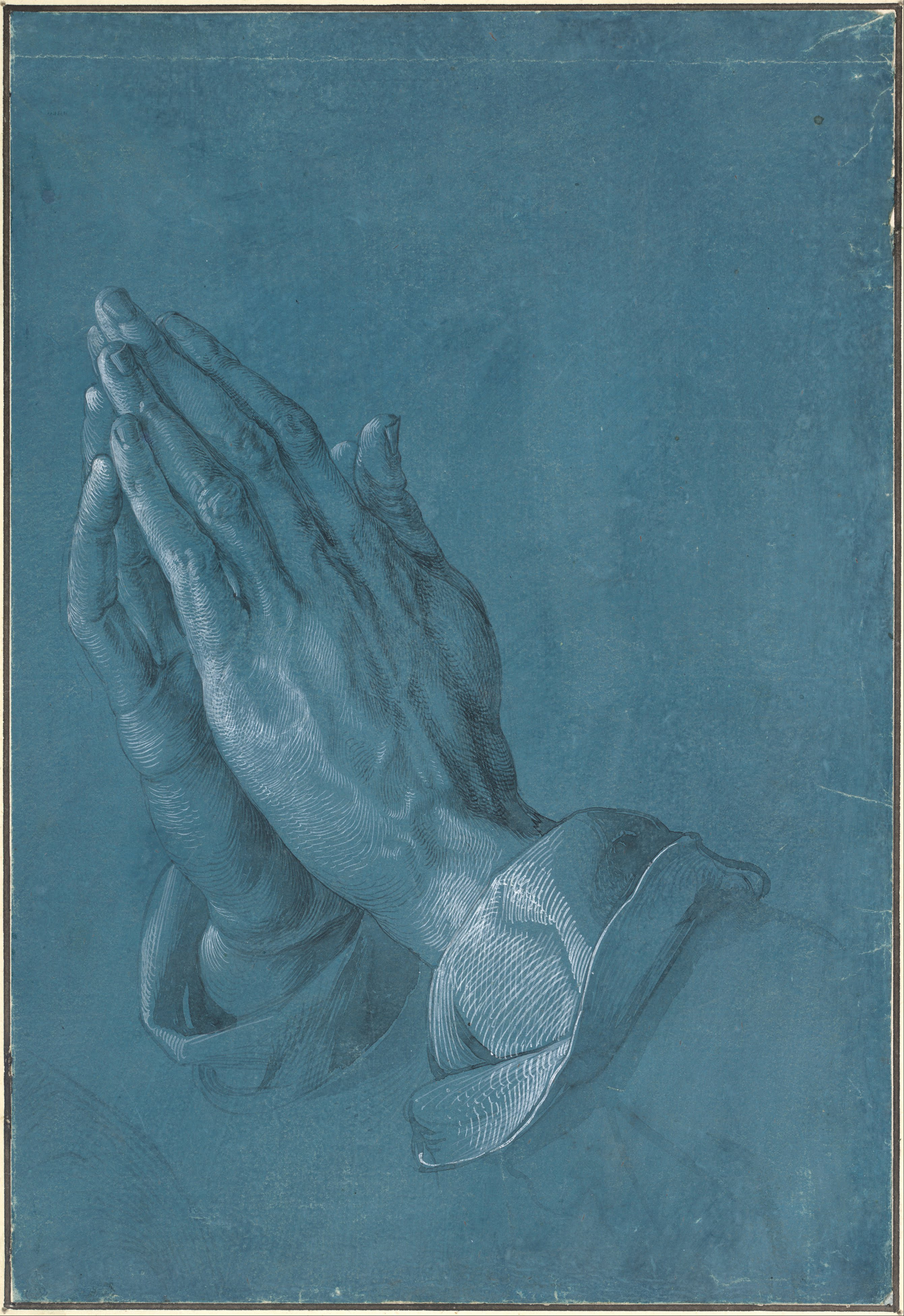

“Dear Lord, help me to not typecast my brother or sister, to not be a stumbling block to a soul striving to reach its potential. Let me be a way forward for those under my charge or care. Allow for me to be that person where another might see what wonderful possibilities have yet to be realized… that I too might by Your grace discern my own capacities during those times when I also might be typecast.”