On Prayer

/“The day when God is absent, when He is silent – that is the beginning of prayer.” Anthony Bloom, Beginning to Pray (1970).

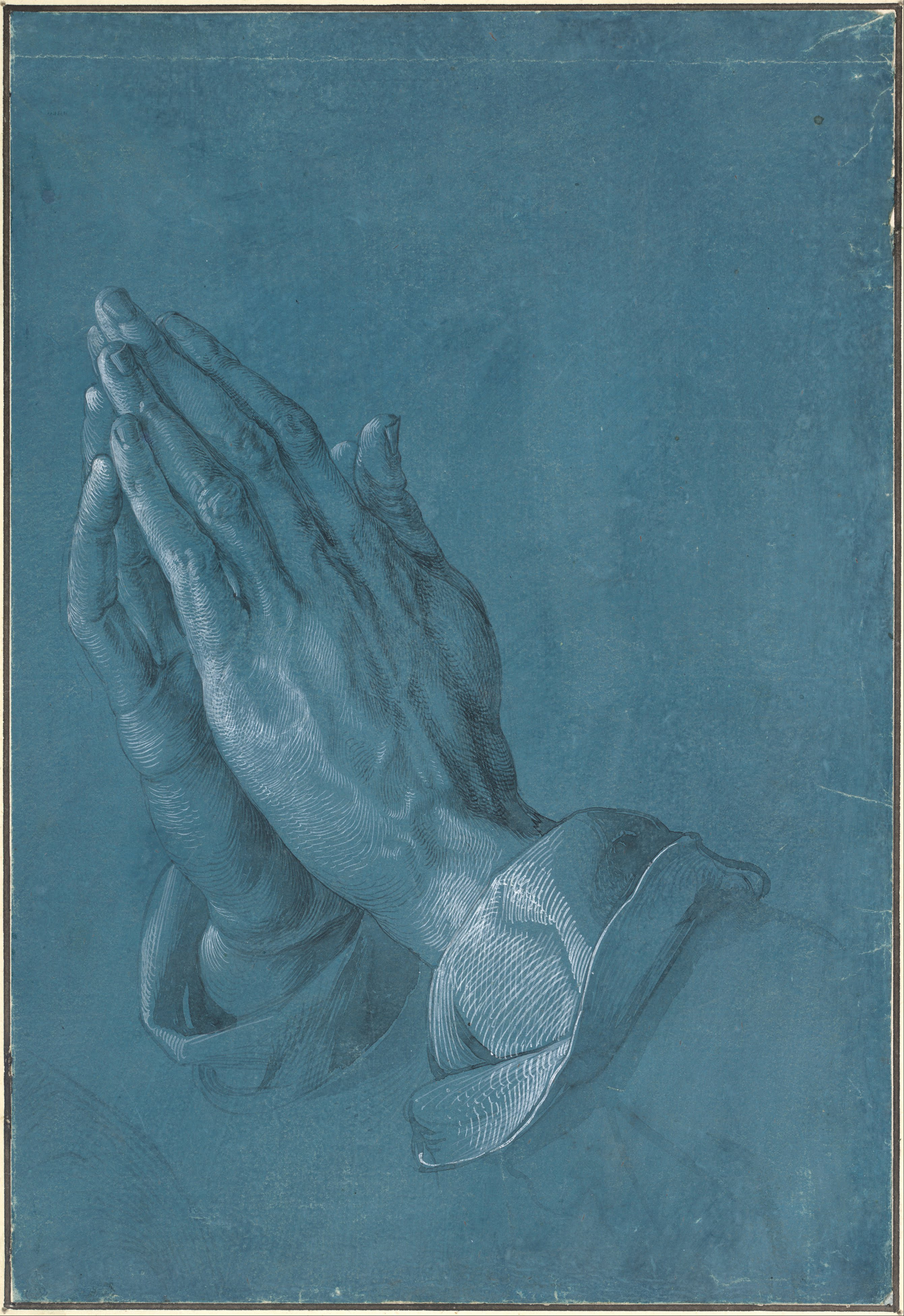

Albrecht Dürer Betende Hände (c. 1508)

There are many definitions to prayer, for similarly to spirituality, it is linked to the realms of the sacred. For most of us, prayer is an interior invocation reaching out to communicate with a divine entity. Ordinarily, this will be our Creator. We need not be spiritual masters or anchorites to approach prayer with confidence, nor is the mastery of any specific technique essential to begin with. Petition, thanksgiving, and worship are characteristic of prayer. The only condition for prayer to be effective is that we might at least be silent and receptive. We are told by those who do pray habitually, that it helps our prayerful state if our hearts are not weighed down by enmity. Even faith itself is not required in the beginning, only the overwhelming desire to speak and to lay open all before the great “I AM” (Ex 3:14). The skies will probably not open and we may not “be surprised by joy”, in fact, not very much might happen. Very likely the only voice we hear coming back will be our own. It is a first step. We have, after all, been separated from this divine source of communication for a long time and our spirit is prone to distraction. Learning to discern the voice of God is not easy. Prayer itself is simple, but the “art of prayer” is a lifetime practice. The Paternoster (Matt 6:9-13) built around the seven petitions of Christ and often called the “perfect prayer” or a “summary of the whole Gospel”, can help us greatly on our quest to learn how to pray. Prayer too commences with an action, a movement into hallowed ground, whether of the spirit or the body. Either way like most things of the spiritual life, acts of charity are one of its primary manifestations, before and after the opening of the heart where it all begins, and in the bowing of the head where it normally starts.